Offside is one of the most fundamental laws of the game. Modern technology has allowed for revisions and tweaks to the finer details (toe-nail offside comes to mind), but the overarching premise remains the same. This has been crucial in the tactical development of the game over the last several years. From low blocks to high press, the position of the defensive line is intrinsic to how a coach wants his team to set up, and the way they want them to play.

The most striking example of recent years has been Hansi Flick’s Barcelona. In his first season, Barça were playing very high and compact, squeezing the pitch and pressing from the front to catch teams out in the build-up phase. It has been discussed at length by fans, journalists and pundits alike, but many still disagree about its efficacy.

The bare facts are that the Catalan side won the domestic treble and reached the Champions League semi-finals in the German coach’s first season in Spanish football. So that would suggest it is a pretty good system. But that semi-final saw them concede seven times to Inter over two legs, a side which was then comprehensively hammered by Luis Enrique’s PSG in the final. Would Barça have reached the final with a different approach? Maybe, but it can also be argued that they got to such a latter stage precisely because of their aggressive style.

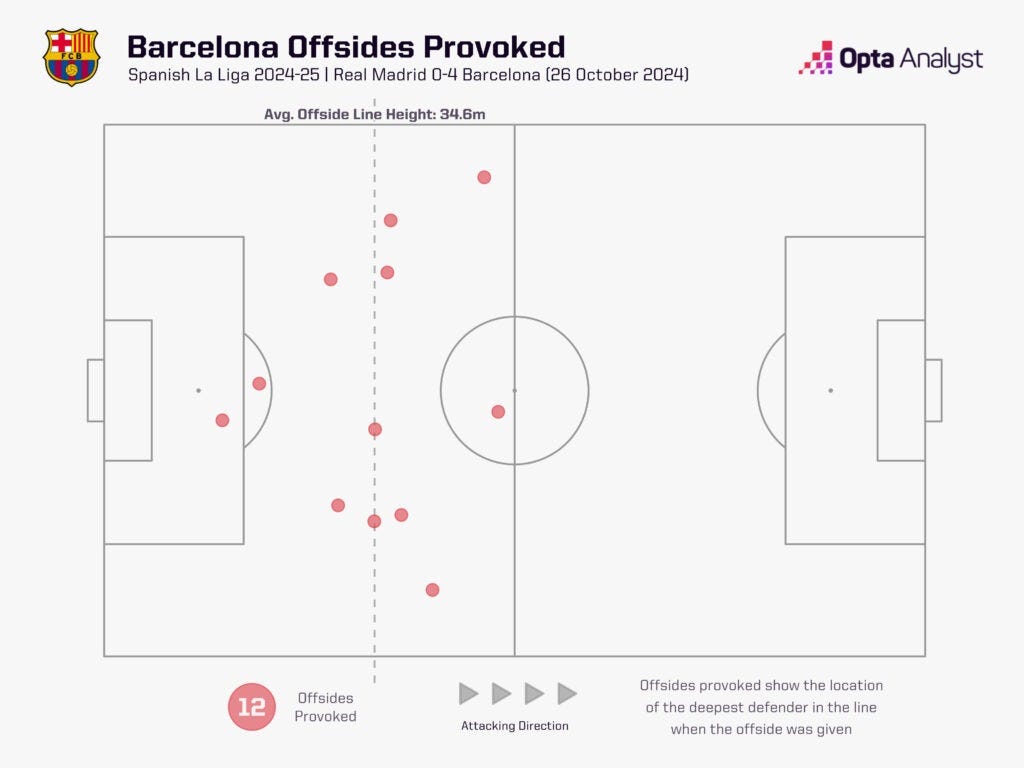

Domestically, Hansi Flick has Real Madrid’s number throughout. In the four Clásicos, Barça put 16 goals past Los Blancos, but it was the first meeting that was the most striking. Arriving at the Santiago Bernabéu, anticipation was high for Kylian Mbappé’s first Clásico, but it was the high line which stole the show. Despite seeming massively exposed against the pace of the Frenchman and that of Vini Jr, Flick insisted it was not as dangerous as it looked. Barcelona caught the Madrid forwards offside a staggering 12 times, and were able to sucker-punch them four times in the second half. In the Copa del Rey final, there were seven Madrid offsides, and then a further five in the reverse league fixture. Although, a caveat was that Mbappé did score a hat-trick in the latest one, which may serve as a warning sign for this campaign.

The number of goals conceded is also a potential red flag for the system. In 70 matches in charge, Flick’s side have conceded two or more goals in a third of those (23/70), and shipped four goals in a game on five occasions (Osasuna, Benfica, Atlético Madrid, Inter and Sevilla in their most recent match). Of course, Barcelona are also an attacking machine, scoring 102 goals on their way to the title last season, plus hitting three or more goals in ten of the 14 Champions League games in the German’s opening campaign.

Are teams getting wiser to the tactic? Is it working as effectively? Can it be maintained across an entire season? Ultimately time will give us a definitive answer, but it is clear the approach requires a high level of fitness and co-ordination. Last season, the veteran Iñigo Martínez was the orchestrator of the defensive line, getting players to move together as if it were a singular being. Much has been made of his departure, especially following the defeat to Sevilla last weekend at the Ramón Sánchez-Pizjuán: It was the Andalusians first league win over Barcelona in a decade, and only their second home win of 2025.

The Basque centre-back did not feature in the first two instances of Barça conceding four (Osasuna and Benfica), but was there for the tougher assignments of Atleti and Inter. Has his absence been overplayed? Or was he a genuinely pivotal piece of the puzzle that took those elements of risk away from the system?

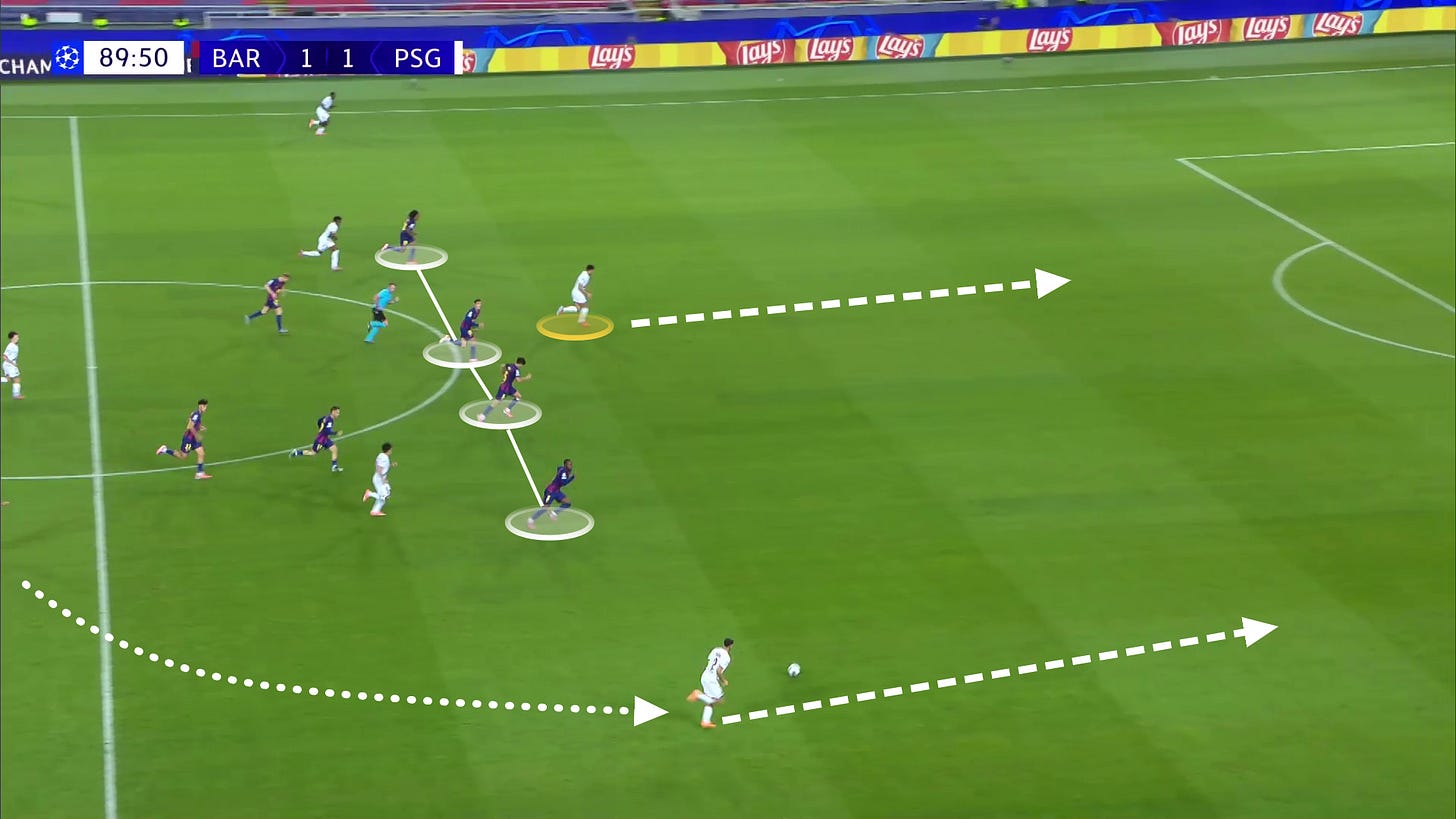

The recent Champions League defeat to PSG also set alarm bells ringing. Achraf Hakimi had an ocean of space to run into late in the contest to set up Gonçalo Ramos for the winner. Former player and CBS analyst Thierry Henry was critical of the approach, arguing the best teams would figure it out:

“You can not play in the Champions League with that high line. I’m sorry, when you play against good teams, you’re going to get exposed”.

Sevilla certainly found a way to hurt the Catalans, repeatedly getting in behind from deeper to be in on goal. Four did not flatter the hosts, and in the intense Seville heat, coach Matías Almeyda insisted on perseverance. At the cooling break, with the score at 1-0, he reinforced the message:

“You cannot lower the intensity or concentration, don’t let them think. Finish it off, you have to finish it”.

Clearly the blueprint was to closely mark the playmakers in the team, stifling their creativity, and then break from deeper when they had the chance. This bold approach could have been suicidal, but it worked, Almeyda admitting it was the “perfect” game. If other teams can be as brave as this, Barcelona’s approach will be tested further. Levante and Rayo have also taken the attack to Barcelona this season: Flick’s men ultimately outscored Los Granotas, but were lucky to escape from Vallecas with a point.

With the first Clásico of this season looming large for Barça, Flick will want to fine tune his approach once more. Without Iñigo to lead the defensive line, and with teams getting wiser and bolder, they could come unstuck. The tactic is ideal to trap the most advanced attackers, like Mbappé in that statistical freak a year ago. But for deeper runs, offside is neutralised, and sometimes it only takes one well-timed run to score a goal. Perfecting the system and mitigating further risks must be the focus for Flick after the international break.