Football's ACL Crisis

More players are suffering each season, but is it solely due to them being overworked?

Real Madrid thrashed Osasuna at the weekend, but the result was overshadowed by Éder Militão having to be carried off the field via a stretcher due to suffering a second ACL tear in as many seasons.

The Brazilian’s club have revealed that he has been diagnosed with a complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament, with the involvement of both menisci in his right leg, meaning that within the span of 18 months, the defender has unfortunately torn both of his ACLs.

Why are we seeing more ACL injuries in football than ever before? What is causing this ill-fated epidemic? Before answering these questions, let’s look at what the ACL actually is, and how it works.

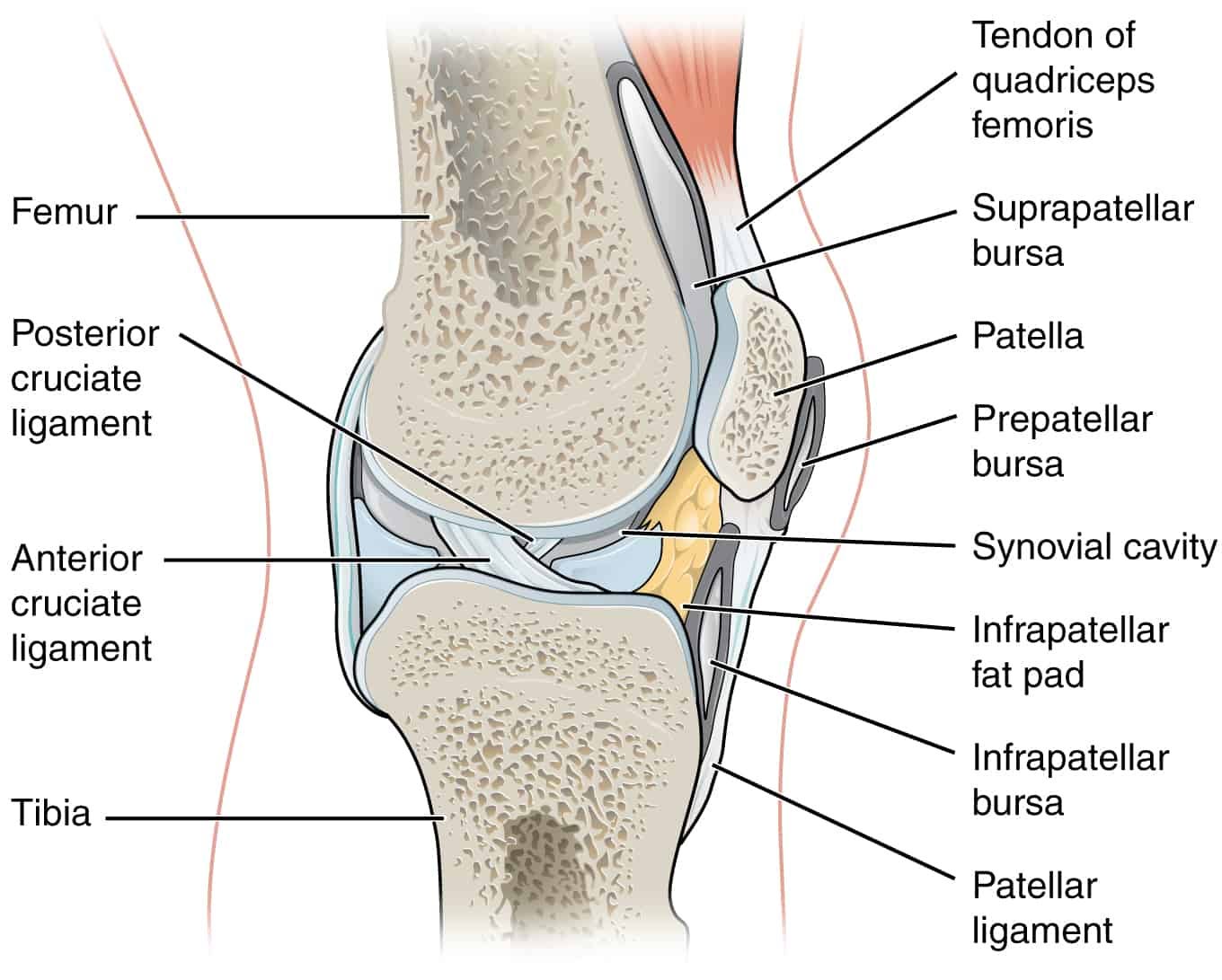

Ligaments are strong bands of tissue that connect one bone to another. The ACL, one of two ligaments that cross in the middle of the knee, connects the thighbone to the shinbone and helps stabilize the knee joint. When the ligament is damaged, there is usually a partial or complete tear of the tissue. A mild injury may stretch the ligament but leave it intact.

Once stress is applied to the knee, there is always a danger of an ACL injury. The main causes are:

Suddenly slowing down and changing direction,

Pivoting with your foot firmly planted,

Landing awkwardly,

Stopping suddenly,

Receiving a direct blow to the knee or having a collision, such as a tackle.

Trying to pinpoint one specific reason for these injuries is a challenge, due to the many ways that they can occur. One study, published in 2020, analysed 134 ACL injuries across 10 seasons of professional football in Italy and found that 56% of them involved contact of some sort, mostly indirect (e.g. to the shoulder), with a small percentage being direct contact to the knee.

The ACL is generally protected from damage that can be caused by decelerations and rapid changes of direction, as there are muscles which help to stabilise the joint. However, once a player is placed at a mechanical disadvantage, such as their studs being stuck in the turf or the existence of a muscular inhibition elsewhere, such as a groin strain or hamstring tightness, then theoretically they are more vulnerable to suffering a serious injury.

The muscles around the ACL are extremely important, as once there is dissonance among the leg muscles, the ACL is in danger. Professor Gordon Mackay, interviewed by The Athletic, said: “If there’s an imbalance in muscle strength between your quadriceps and your hamstrings, that may in certain situations leave you more vulnerable to a cruciate injury.”

Many footballers have started to blame their schedules for these injuries, and they have reason to do so, as it is generally understood that athletes who train more than 10 hours per week have a greater chance of ACL injury. Additionally, fatigue can reduce muscle strength and change how the lower limbs move, which can increase the risk of injury.

However, the most obvious risk factor for ACL injuries by far is being female, says Dr Christopher Kaeding, who was also interviewed by The Athletic. Females are anywhere from two to eight times as likely to suffer an ACL injury than males.

While it is still a topic that requires a lot of research, it’s often assumed that the increased risk for females comes down to hormonal and anatomical differences, with females having wider pelvises and completely different biomechanics.

Another one of the primary risk factors for serious ACL injuries is the playing surface; synthetic turf can cause the foot to get stuck when planted, which as previously mentioned, leads to more stress on the knee.

As concerns gather pace across the sporting world, not just football, researchers have begun looking at what can be done to protect the players. In the meantime, players such as Rodri and Dani Carvajal have been protesting against the heavy-duty schedules that footballers have to adhere to nowadays. Since their protests, these two players have both unfortunately been sidelined for the remainder of the current season with respective ACL injuries.

UEFA’s goal is to publish a consensus on ACL injury prevention and management, and an ACL injury prevention programme. “The consensus,” say UEFA, “will provide evidence-based guidelines on topics ranging from ACL injury prevention and common risk factors to injury mechanisms and optimal return-to-play strategies, all tailored specifically to women’s football.”

To read more about The Athletic’s interviews with Professor Gordon Mackay and Dr Christopher Kaeding, check out their article: https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5120100/2023/12/08/acl-crisis-premier-league-wsl/